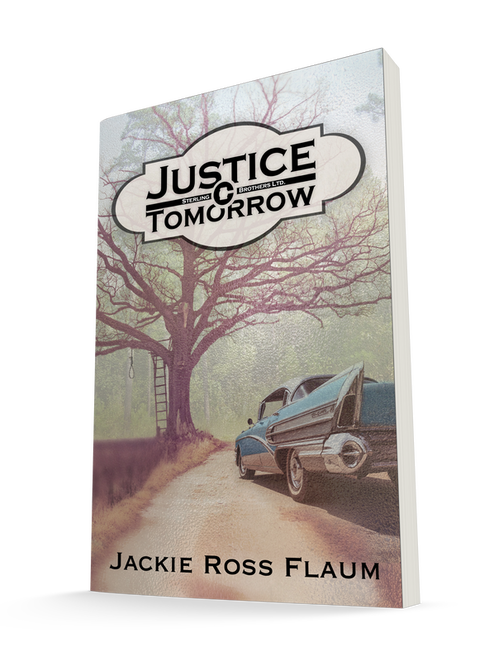

Meet Madeline Sterling...1963

A big black limousine appeared suddenly out of the swirling snow and icy winds. With headlights shining and windows fogging, it idled on the street alone like a metallic monster poised to ravage the white trees, frozen bushes, and middle-class Boston brownstones. Eighteen-year-old Madeline Sterling sucked in a startled breath through her wool muffler. Whoever was desperate to brave the surprise March blizzard hadn’t parked there long. The limo’s roof was almost bare. She leaned into the wind and trudged closer to her parents’ house, her long coat flapping furiously against her legs. The trip from Radcliffe College had been tedious. Now this car parked out front in a storm. She pulled her red striped muffler higher over her chin to hide a new bruise and keep her warmer. Had something happened to Danny? She walked a little faster. Her older brother served in a special unit of the U.S. Marines. Her muscles tensed until it dawned on her the military wouldn’t bring bad news in a limousine. Besides, whoever was in the car was expected. The sidewalk by the car and the walk to the steps of her house were shoveled and salted. Her father would never do such a thing unless the president of Harvard University was coming to the home of his humble history professor. Even the “Integration Now” sign which irritated the neighbors had been dusted off. So the visitor wasn’t from Harvard’s administration. Maybe the guest was a favored alum. Alan Sterling often hosted his students, fellow scholars, and those hoping he would consult with them on a project. Many of them had wealthy families. Sometimes she’d come home to find a loud debate had spilled over from the study to the living room. Invariably her father would draw her into the fray and become red-faced if she offered an argument opposed to his. She wouldn’t be caught in a mad discussion. Not today. While she was at a civil rights demonstration on Harvard’s campus last week someone threw a rock at her. More than her chin hurt. She expected to be chased off campus by the pigs, but not by students. More than anything she needed the warmth of home, the taste of honey-flavored hot tea, and a pep talk. Following the path cleared for the guest, Madeline hurried to the stairs, noting the small, rapidly disappearing footprints which preceded her. At the front door she paused to wipe her boots. “I’m home.” She trampled her boots once again on mat inside and slung her olive drab knapsack against the foyer wall next to the coat rack. She stuffed her gloves in her coat pocket. “Daddy! Mom!” “You dinna need to shout.” Professor Sterling, black Irish hair falling across his face and down his back, stuck his head out of the living room then disappeared back inside. The pipe clamped between his teeth had gone out. Madeline frowned. Her mother emerged from the living room. “Madeline, you have a visitor.” Dread swamped her. Radcliffe had expelled her for activism. She’d been warned by the administration once. Her father was so respected in the academic community it wasn’t surprising the college would send someone to tell him first. Sterling yanked the wool stocking cap from her red curls, jammed it in her pocket, and tossed her coat in the direction of the coat rack. As it did nine times out of ten her coat caught on a hook. She put a hand over the bruise on her chin, hoping to hide it. Katherine Sterling greeted her daughter in the foyer with a long, fierce hug that ratchet up Madeline’s anxiety. Then she brushed her daughter’s hand away and examined the small purplish bruise. “I fell.” “Hm-m.” Her mother’s lips pursed. “You were never a clumsy child before. Anybody else hurt in y’all’s demonstration at Harvard?” Her mother’s Mississippi roots were showing. Madeline cringed. “Come on, honey.” Katherine slipped her arm around Madeline’s waist and ushered her into the living room. A fire burned in the grate, occasionally popping sparks onto the green hearth rug. She steered her daughter toward an older woman seated in the chair reserved for the professor’s guests of honor. Her father, who sat on the sofa opposite the guest, stood. Her visitor offered a welcoming smile. Older than Sterling’s mother by at least a decade, the woman extended a hand with a large gold-crested ring on it. She had chestnut brown hair fashionably styled to suit her oval face. While she wore a haughty look of wealth and breeding, her green eyes glowed with such passionate determination Sterling felt drawn to her. “Madeline, I’d like you to meet Mrs. Elizabeth Woolworth,” said her father. “Few at Harvard or Radcliffe know it, but she is one of our most valued patrons. She and her late husband—well, I won’t embarrass her further by reciting what they’ve done for civil rights and higher education.” “Alan, you are too kind,” said the woman as she took Madeline’s hand. “I’m pleased to meet you at last.” “Your mother and I’ll be in the kitchen.” Alan got up and as he left he squeezed his daughter’s shoulder. Madeline’s puzzled eyes followed her father’s exit. “I know this seems a bit confusing,” Mrs. Woolworth said. “What I have to tell you is for your ears alone.” Madeline’s eyes widened. “Sit. We have a lot to discuss.” The woman settled into her place on the floral Queen Ann chair as Madeline perched on the sofa. “I represent a civil rights organization called Justice Tomorrow, and we’d like you to become one of our agents.” Agent? Excitement sizzled through Sterling. Her cheeks flushed with joy. Was Justice Tomorrow an arm of the FBI? Had Director J. Edgar Hoover been worn down by all her letters and applications? Two agents had asked around the neighborhood about her last fall. Perhaps they were doing background checks not snooping on a civil rights activist. “Justice Tomorrow is a highly secret, private organization with a sensitive mission,” the woman went on. “We recruit, train and dispatch college-age investigators to the Deep South. Their job is to identify and collect evidence against killers of civil rights activists.” Sterling’s mouth dropped open. “Why? None of these murderers will be convicted in a Southern court.” “Alas, you are correct. We can prosecute some of them. But most of our cases must wait until we have a more enlightened South. Our agents gather and preserve evidence — quietly, discreetly, cautiously— until the day these killers can be convicted in a Southern courtroom. Murder has no statute of limitations.” “How can you possibly do that?” For the next hour Mrs. Woolworth told Madeline of a network in southern towns, men and women afraid to act on their own, but willing to help. She outlined a well-funded operation with extraordinary resources to help its young detectives. People in Washington and elsewhere, she explained, with influence and strong beliefs. “I don’t know anything about investigating murders,” Madeline admitted. “You’re daring and curious — we can teach you. There’s a six-weeks training camp with former soldiers and, well, others. We believe college-age investigators’ natural curiosity will be an asset—and a little protection. After all, who would suspect a college student could find clues to send a murderer to prison? You will be a fully qualified detective when your service is done. The FBI would be glad to have such an investigator. . . J. Edgar Hoover can’t live forever.” Madeline wanted to be cautious, but it was too late. “We require two years of service,” the woman said then noted Madeline’s upraised eyebrow. “We put a great deal of money and effort into training you and your team.” “Team?” “Fellow students. Negro and white. Male and female. Each infiltrates his own community near the crime, gathers information, and withdraws without fuss or bother. Here.” She handed over a large white envelope. Madeline had butterflies in her stomach. “Your itinerary and airline tickets. If you make your first flight, we will assume you have accepted our offer.” Mrs. Woolworth stood, gathered her coat, and picked up her large black purse. “Most parents feel Justice Tomorrow is too dangerous.” Madeline knew black protesters and whites who dared stand with them were threatened and beaten in Alabama, Georgia, and her grandparents’ hometown of Tupelo, Mississippi. “But you just said your agents withdraw without fuss or bother.” Mrs. Woolworth smiled, adjusted her coat around her, and soon the wind of the storm closed the front door with a loud “bam.” |

|