Meet Socrates Gray...1961

Socrates Gray knew they would come at him sometime during his time at Yale University. He’d endured plenty of racial slights and slurs in his three years on the New Haven campus, but he always expected a physical attack that left him bruised and bloodied. Or dead. Still, it surprised him when two white men stepped from the shadows of the trees and blocked his path from the apartment he shared with his younger brother. His eyes swept the park-like area warming in the spring afternoon sun. Empty. As he knew it would be. The men had planned the assault. The taller and younger of the two men, had a hand—the one carrying his weapon no doubt—behind his back. The men didn’t hide their faces, which meant they came to kill so he couldn’t identify them. Not that the New Haven, Connecticut police would really try to find to those who killed or brutalized a black student. “Socrates Gray?” The older man asked. His green eyes seemed to sparkle in the sun. He was much shorter than his companion or Gray. His shoulders squared, his lips pursed, and he appeared like a butler announcing dinner rather than an assassin. Gray had learned to be wary of appearances. Some of the most proper, preppy-looking Yalies had peppered him with insults and threats. “Gray. Call me Gray.” His weight shifting to his back foot. “I’m Arthur Woolworth. Might we have a word?” His hand swept to a nearby park bench. “I’m late. . .” Gray gathered his breath. For the first time he noticed they both wore suits. And the taller man’s hands were empty. No weapons. “I-I’m late for class.” “It won’t take long, I promise. We have an extraordinary offer for you to consider,” said Woolworth. “If you say no, you can continue on to class—or we will drive you if you wish.” “W-what—What kind of offer?” Woolworth nodded to his companion and the taller man stepped aside, out of earshot. His eyes, however, scanned the area as though an assault was imminent. “Please, can we sit. I’m not as young as I used to be and the blasted sun isn’t as warm as I’d hoped.” Before he sat, Woolworth flipped back his dark wool coat, reached into his hip pocket, and took out a billfold. He flipped through the contents a moment, then founded a picture to hand Gray. The photo had white rippled edges like older Kodak pictures and there was no writing on the back. When Gray turned it over, he gasped. “I see you recognize two of the people in the picture,” Woolworth said. Gray sat on the bench. The Eiffel Tower in Paris filled the grainy background of the photo. Six, no eight, young people laughed at the camera. Two of them were his parents. Another was the younger version of the man in front of him. “Your mother was so fair skinned she passed for white in Paris,” Woolworth said. “She thought it was funny. She actually made a game of it when we were around Americans. Florence—your mother—was daring. What she endured and the horrible stories she told..." “She was a wonderful storyteller. My father, brother and I loved to hear her spin a yarn.” Gray stared at the photo, felt his eyes burn. “Well, we were, all of us, idealists, philosophers, painters, and writers who would change the world with our vision. Back then we felt invincible. And we had plans. Your father came late to our gang of adventurers. Your mother met him—.” “In a French café opposite the Sorbonne where he was a student,” Gray finished. “As the war clouds gathered, all of us went home. First one, then another. They followed their dream of educating young Negroes in the South, hoping the South would become, well, as free and accepting as Paris. I went to war then followed dreams of a practical nature.You may recognize others in the picture as wealthy, influential people now. One is very well connected in government.” For a moment Woolworth studied his bony hands popping with blue veins. “I still paint a little.” “You knew them.” Gray couldn’t believe his luck. Someone who could actually speak of his parents, what they were like, how they moved, who they loved. Woolworth nodded. “For what it’s worth, even then I tried to talk them out of returning to the South after the war. Nothing changed there, even for men like your father who fought Hitler in the same trenches as whites. They were…they were warriors. I am sorry for you and your brother. I never knew of your existence until later. Much later.” “We moved in with my aunt and kept our heads down. She tried to turn us into God-fearing Christians, who forgave our enemies.” Gray swallowed hard. “Too much to forgive.” Woolworth drew in a breath. “You want them punished. Not just the ones who killed your parents, but all those who burned, beat, murdered and stole from Negroes.” “Yes.” Gray’s hands had clenched into fists. “Yes.” For a moment the older man pursed his lips and thought. “Have you studied Gandhi here at my Alma mater?” “Of course.” “Do you follow the young Baptist preacher, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. who went to India to meet Gandhi and study his method of non-violent protest?” Woolworth asked. Gray nodded, his earlier fear now turning to impatience. “Do you agree with it?” “I-I can see where it can be effective. I respect the brother.” The smell of car exhaust and the tickle of pollen in his nose had him reaching for his white handkerchief. A man always carried a pocket knife and a handkerchief, his father had taught him. Woolworth smiled at him. “You’d prefer a more, ah, active approach.” “I suppose.” “I believe my proposal will interest you, although, I warn you, if you lack patience and self-control you will find yourself ill-suited for what I offer.” Gray laughed. “The black American has more self-control than any other human. We have had it beaten into us, into our genes, over the course of a century. But patience? My patience is wearing thin with segregation and this conversation. Either make your proposal, Mr. Woolworth, or let’s talk of my parents. I would appreciate hearing what they were like when they were my age.” “Very well.” Woolworth leaned back and crossed his legs. “We can do both at once. I represent a secret organization which will equip young investigators to find evidence against the killers of black activists in the South. I want you to become one of our investigators.” Gray sat up straight. His jaw dropped a little. “Once this evidence is gathered it will be store securely until the day justice can be achieved in a Southern courtroom.” “So, it will never be used.” Gray snorted. Woolworth wagged his finger. “You forget, murder has no statute of limitation.” For a moment Gray stayed silent. “It’s a suicide mission.” Woolworth hummed his agreement. “Powerful men and women have spent the last year setting up an extensive network of support.You would be surprised to learn their names. Safe houses. Secure hospitals. Supporters in every town you are sent to. Research at your fingertips. You will be trained and re-trained in skills you need—interrogation, self-defense, evidence collection and storage. You’ll work in teams of young men and women. White and black.” Now Gray scoffed, “You think you’ll find a white woman to join?” “The first class of recruits has one training now.” Gray rose, scratched his chin. He could hear blood pounding in his ear, feel urgency and sense of purpose rise in him. “What about my brother, Aristotle?” Woolworth uncrossed his legs. “Tell him you have had a job offer as a salesman out west. I’ll give you a business card to show him. He can get word to you through a telephone number that is manned at all times. He has to finish his studies.” “Yes, my parents would want that,” Gray murmured. “You can not tell Aristotle the true nature of your work. Lives will depend on secrecy.” Woolworth chuckled. “We even use code words, secret mail drops. The stuff of spies.” “What do my parents have to do with this?” Gray asked. “It was their idea. Their vision. Justice Tomorrow.” +++ The battered old tow truck strained and slipped on the creek mud before it got enough grip on the land to haul the car out of the brackish South Carolina water. As it emerged from Bass Creek’s depths, Gray and the rest of the black men overlooking the creek murmured and muttered among themselves. Some of the men sharecropping Aker’s land thought it belonged to one of the white ladies in town. She must a took the curve too fast, crashed through the metal guardrail, and sailed into the creek. The wild young Lieke boy drowned like that five years ago before the guardrail went up. Like scavenger birds the men perched on the embankment well out of the sheriff’s way to see if they could be the first to pick over the tragedy and carry the news home. “Come on, boys, let’s go sees about this,” said a teenager who worked with the Aker’s men. The ghoulish group staggered in ones and twos closer to the truck. “It ain’t gwanna hold,” predicted one of the men. “Truck ain’t setting right.” “It’ll hold,” said another. “There’s chocks against the back tires to steady it.” Sure enough, the closer the group maneuvered to the scene the better they could see details like the stops behind the tow truck’s rear tires. The winch on the truck tightened and ground. With a mighty suck-and-splash sound the green and white Ford sedan emerged from the muddy creek water and onto the bank. The truck jerked to a stop and released the winch. The car body shuddered to a stop on the edge of the water. Twenty-one-year-old Gray gripped his belt buckle like his pants were going to fall off any minute. He had lost a lot of weight working undercover in the fields and sweeping the Post Office in Raines at night. But he tightened the belt in hopes he could keep from heaving up his lunch. For the first time in weeks he was glad of the heat and humidity—it covered how he’d broken into a sweat from the moment he’d seen the car. The sheriff’s two deputies swarmed it like the wreck was going to crank up and drive off. “North Carolina plates,” one deputy called. In his excitement his voice rose loud enough to wake the dead. “Come lookee here! The plates, the bumper—hell, the whole back end of the car looks like it was rammed into a bunch a times. Look at them dents. And no rust on a one. Ever scrape and dent looks new. Someone kept bumping and bumping and —I bet it finally knocked the car off the curve and—.” “Shut the hell up, Norm,” shouted the sheriff. He swatted a buzzing insect. “Who’s got the goddamn camera?” Another deputy with a black camera around his neck hurried over and aimed into the car where the sheriff pointed. Norm came around to the driver’s side and, if possible, turned whiter than he was on Sunday mornings. He and the sheriff conferred. More photos were taken from every angle. A siren wailed. An ambulance stopped at the top of the creek embankment, and for a moment Gray harbored the hope the person in the car lived. Two men popped out and ran to the back for the stretcher. The tension on the embankment ran high among the black sharecroppers, workers, and tradesmen. Was there someone in the car? Was he alive? Was the car run off the road as the deputy suggested? Who would want to do that? Was he white or black? Just then sheriff yanked open the driver’s side door. Water gushed out, carrying a small brown leather sling bag to rest half in and half out of the car door. Unconcerned, Norm and the sheriff wrestled a body out of the car, while the deputy taking pictures captured the moments for later use in court. “White lady,” announced the antsy teenager by Gray. Another man craned his neck. “How you know? I don’t see nuthing.” “Light colored hair. Long. I seen that!” The young man pounded his chest with one hand. Gray backed away from the creek. It was his partner. He didn’t need to see anymore or keep fanning the tiny flame of hope that somehow her car had been stolen. The woman in the sedan was twenty-year-old, a veteran of four missions, one of the original members of Justice Tomorrow. She had been late for a rendezvous at their safe house. Gray knew something was wrong then. She’d been the one to signal for the meet. Gray slapped one of the men on the shoulder. “Ben, I gotta git. Take your uncle Joe this here money. I owes him this last payment on his old Buick .” Gray reached in his pocket and handed over a wad of bills. He kept back $3 for gas. Ben’s eyes grew wide. “He done sold the Buick? Man, he been working on that car five years.” “It runnin’ now. And it’s all mine. Tell him I’ll walk over tomorrow and git it,” Gray said. “I pays on time like I says I will.” “I’ll do that.” Ben stuffed the money in his pocket without counting it, and shook his head. “Never figured he’d sell the Buick.” “Hell, he’s got a truck,” said another man who couldn’t stop watching the ambulance attendants load the body onto the stretcher. “My aunt had her heart set on pullin’ up to church in that car someday,” Ben said. “I gotta git to work, boys. Holler at you later. Thanks, Ben.” Gray waved as he set off toward town at a trot. Thank God, Ben’s uncle lived in the same direction and around the bend in the two lane road. The death of Lucille Cogsworth, Vassar College graduate and lover of country music, would not be a secret long. The same people who killed her were likely hunting him right now. Or waiting to ambush him when he got to work at the Post Office. His story would give Ben’s uncle Joe cover for letting him take off in the Buick. Hopefully, Gray had enough time to drive to the next safe house in the Buick, pick up another car, and get out of state. He waited until he was certain nobody could see, then Gray abruptly turned and ran down a country lane toward Ben’s uncle. It was almost a mile off the road. He prayed he was not to late to escape, to report back to Woolworth. And put Lucille Cogsworth’s name on the list of those who died in the service of civil rights. |

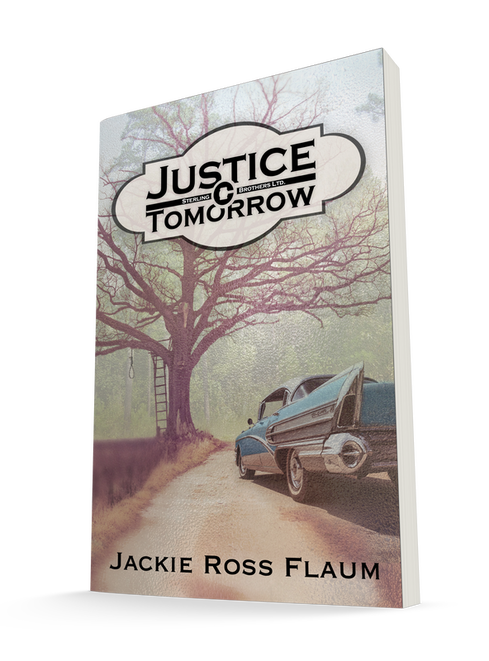

|